Jan 23, 2024

The ski touring trip that did not go as planned

Peter Nilsson tells the story about a ski touring trip to Lyngen, Norway, where the skiers had one plan and nature had another one.

For weeks, I had been following the weather forecasts. The snow conditions in Northern Norway were improving as our departure date approached. We were headed to the Lyngen Alps. Our goal was to make big descents in steep terrain, and the conditions were starting to look really good. For those willing to earn their vertical meters by their own effort, the opportunities in the area were virtually endless. Additionally, we were going to be a great group, the snow cover was cold and stable, and the long days of spring when the sun never seems to set had finally arrived. Expectations were high.

As we headed north, the situation changed. The temperature rapidly rose throughout the region, and the previously stable snow cover became treacherous. It left us with two options. Either to stay in flat terrain, where the snow would likely be poor, but the avalanche risk would be low. The other option was to find cold snow. There was a high-altitude run sheltered from the sun in the north, where the warmth might not have reached yet, deep into a protected valley that could be an alternative. It would be difficult to access, and we would have to walk quite far to get there, but there was a small chance that the snow would still be good. We took the chance.

The road turned out to be long, alright. What was supposed to be an easy approach along a well-prepared snowmobile trail turned into something completely different. Spring had hit Northern Norway with full force. Streams opened up, the lakes' ice melted, and the snowmobile trail we had intended to follow had completely disappeared. Instead, we zigzagged through the remaining snow in the valley, forced to take long detours around large areas of bare ground. Over rocky outcrops and open streams. Further into the valley, the streams became more numerous and larger, and we had to navigate through a labyrinth of still-intact snow bridges.

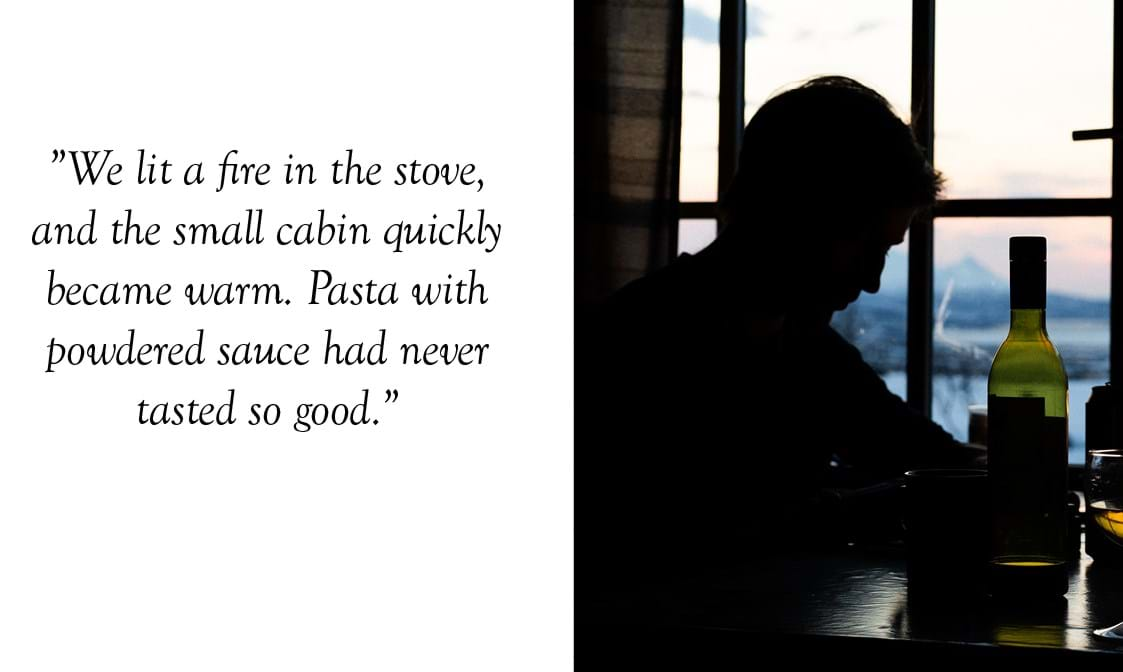

Much later than planned, we finally arrived. We lit a fire in the stove, and the small cabin quickly became warm. Pasta with powdered sauce had never tasted so good. Until the very end, it was uncertain whether we could make it all the way in, but we succeeded in the end. We got there. Sitting in our base layers and seeing the weak evening light reflecting off the mountains outside, it felt like we had already won. Just being there was worth all the trouble. It felt like everything from this point on would be a bonus.

Much later than planned, we finally arrived. We lit a fire in the stove, and the small cabin quickly became warm. Pasta with powdered sauce had never tasted so good. Until the very end, it was uncertain whether we could make it all the way in, but we succeeded in the end. We got there. Sitting in our base layers and seeing the weak evening light reflecting off the mountains outside, it felt like we had already won. Just being there was worth all the trouble. It felt like everything from this point on would be a bonus.

The next day, we headed up into the mountains. The snow was warm. The streams rushed outside the cabin. We aimed for a chute that descended straight into the fall line, carved out of the rocks from one of the peaks above the cabin. 500 vertical meters of steep skiing that led to a vast open glacier. Once on the glacier, we could see that it was warm even at higher altitudes. Loose snow had started rolling down the mountain slopes, and we could see remnants of spontaneous avalanches. Bad signs.

The next day, we headed up into the mountains. The snow was warm. The streams rushed outside the cabin. We aimed for a chute that descended straight into the fall line, carved out of the rocks from one of the peaks above the cabin. 500 vertical meters of steep skiing that led to a vast open glacier. Once on the glacier, we could see that it was warm even at higher altitudes. Loose snow had started rolling down the mountain slopes, and we could see remnants of spontaneous avalanches. Bad signs.

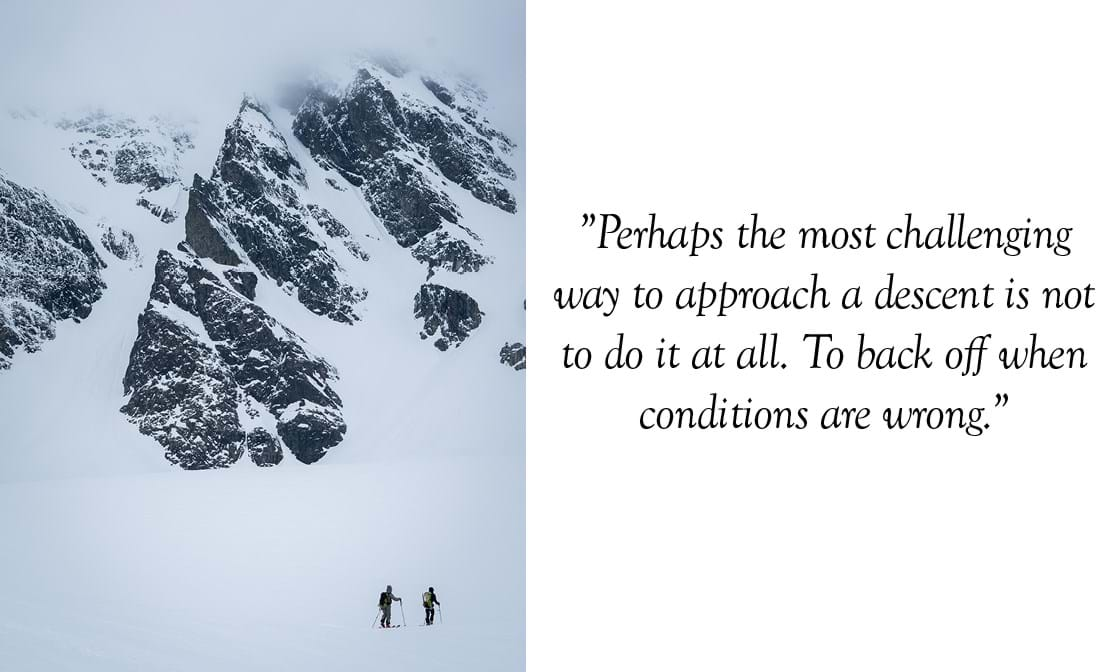

By this point, it was clear that our planned descent would also be affected by the warmth. We also knew that there was a risky layer deeper in the snow, which would likely release under pressure. In a chute like this, that couldn't happen. Even though all the warning signs were there, and everyone agreed that we shouldn't go, it's interesting how difficult it was to actually make the final decision. To call it off.

By this point, it was clear that our planned descent would also be affected by the warmth. We also knew that there was a risky layer deeper in the snow, which would likely release under pressure. In a chute like this, that couldn't happen. Even though all the warning signs were there, and everyone agreed that we shouldn't go, it's interesting how difficult it was to actually make the final decision. To call it off.

Perhaps the most challenging way to approach a descent is not to do it at all. To back off when conditions are wrong. Especially when you've invested a lot in getting there. Hopes, dreams, and expectations, but also time, effort, and money. At the same time, there's something beautiful in it. Nature's conditions set the limits. We have to act accordingly. Limitations that prevent us from doing what we planned also open up new opportunities to learn and think differently.

Once again, we made a plan B. Roped up, we followed the glacier upwards towards the pass into the next valley. Since we were no longer going to the summit, we suddenly had plenty of time to sit and enjoy the moment. Sheltered behind a ridge, we had a clear view of the surroundings. Steep mountain slopes and jagged peaks in all directions. I've had snacks in worse places.

Once again, we made a plan B. Roped up, we followed the glacier upwards towards the pass into the next valley. Since we were no longer going to the summit, we suddenly had plenty of time to sit and enjoy the moment. Sheltered behind a ridge, we had a clear view of the surroundings. Steep mountain slopes and jagged peaks in all directions. I've had snacks in worse places.

The descent turned out to be something different than what we had planned. Instead of the steep chute we had aimed for, we skied down a several-kilometer-long open glacier in the adjacent valley. The wind was tearing at our clothes. The descent seemed never-ending, the size of the surroundings deceived the eyes. It's easy to feel small in that kind of environment, humble in the face of the mountains. A powerful experience. For a last-resort plan, it wasn't so bad after all. It was evening by the time we returned to the cabin. Boots came off. A dry base layer went on. Someone pulled out a hidden bag of chips from a sled, and life suddenly felt unreasonably good again.

We were satisfied. We didn't get what we came for, but we really gave it a chance. Based on the situation, we made the best of what we had and made good decisions together. We kept our spirits up and supported each other. Even though it was tough to back away from the descent we had hoped for, we all agreed that it was the right choice. It leaves a nice feeling in the gut. The trip didn't turn out as planned, but I'm very glad we went. Skiing isn't just about ticking off runs on demand. Sometimes, the journey there can be just as important. It shouldn't always be so easy; otherwise, it wouldn't be an adventure.

The steep chutes are still there. We'll get them next time.

/Peter Nilsson

Heyday: An alpine shell layer

Discover Heyday, a state-of-the-art performance shell working in harmony with your body on your most demanding adventures. Our Made-to-Move design technique in combination with the strong, stretchy fabric ensures full freedom of movement.

Serious mountaineering shell jacket designed for a rugged life in the mountains. 100% circular, fully featured and super-durable. 3D shaped for freedom of movement and optimal microclimate.

1 000.00 CAD

600.00 CAD

Houdini Sportswear. All rights reserved.